It’s Tuesday, which means it’s time for another post from America’s alternate realities! So far, we’ve seen how close the young nation came to being torn apart by a weak central government and a debt crisis. Thanks to the Constitution and Hamilton and Jefferson’s compromise, we successfully avoided those dystopian timelines. This week, we’ll peek into another universe where America’s first Commander-in-Chief is a little less altruistic…

Don’t forget you can also re-read my original post on the 1796 election from our current reality.

The Last Four Years

Despite his historic reputation as a unifying leader, George Washington’s presidency was largely defined by intense partisan debates between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. The Federalists, led by Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton, believed in a strong and active central government to promote the common good of the nation. Democratic-Republicans, like Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, instead believed limited government was necessary to protect the rights of states and individuals. In Washington’s first term, Hamilton and Jefferson reached an important compromise. The federal government would assume states debts in exchange for moving the national capital south to the Virginia-Maryland border. Although one crisis had been averted, the dividing lines for the first political parties had been set.

The next major issue that Washington faced was in foreign policy. Following America’s lead, the French Revolution brought the fight for liberty to Europe. This also meant war between the new French Republic and Great Britain. The United States was in a precarious position as an important trading partner of both world powers. As tensions rose, the British navy began capturing American merchant ships en route to French territories. Democratic-Republicans were furious. They felt that the US owed France a moral debt for their aid during the American Revolution. The fact that British troops had attacked Americans was cause for war. Federalists, on the other hand, believed that America’s trading relationship with Britain was too important to risk. They argued that the French had not supported the American Revolution out of the kindness of their hearts, but rather, to damage their geopolitical rival.

Washington sided with the Federalists and hoped to remain neutral in Europe’s wars. He felt that the French had been unfairly attempting to persuade the American public to support a war that they had no real stake in. He sent Chief Justice John Jay to negotiate with Britain. In the resulting “Jay’s Treaty” (heavily influenced by Hamilton), the US promised to follow British maritime rules during the war, and both nations became “favored trading partners.” It also settled outstanding issues over the Canadian border, forts in the Great Lakes region, and debts from the Revolution. The treaty was unsurprisingly controversial and Washington faced harsh criticism from the Democratic-Republican press. The experience solidified his belief that partisan politics was one of the biggest threats to the nation.

Major Issues

As Washington’s second term came to a close, he needed to decide if he would run for a third term or step down. Although he had always been reluctant to hold power (his true desire was to remain peacefully at his home in Mount Vernon), relinquishing the presidency would be an unprecedented political move at the time. Britain’s King George III even speculated that stepping down would make Washington “the greatest man in the world.”

The limits of presidential power had been a source of controversy since the drafting of the Constitution. Hamilton, the document’s chief architect, believed that a strong executive (originally a “monarch”) was necessary to balance the power held by Congress. Although he never argued for it publicly, he even considered the idea that the position would be hereditary, rather than elected. Importantly, he also believed that this person should serve for life. In fact, despite the obvious issues Americans had with the monarchy, many still felt that Britain had the best system of government. It was largely expected that the US would follow the same blueprint.

So far, as president, Washington had carefully commanded respect while avoiding aristocratic elitism. But a consistent head-of-state might be necessary to thwart the worst impulses of congressional partisans.

~The Time Warp~

As he did on most issues, Washington sided with Hamilton. He chose to remain in office to be the strong leader that America needed. Otherwise, he feared, European powers would drag the United States into war. Although he longed for retirement, he felt that he was doing what was best for his country.

The Winner

Another unanimous decision! Even though the Jay Treaty had been controversial, no one could kick the most famous man in America out of office. Washington established the precedent that presidents would unofficially serve for life, with ceremonial “elections” every four years.

The Future

Washington remained president until his death in 1799. Because the Constitution did not specify the line of succession, Congress decided to simply hold a new presidential election. As originally intended, electors were appointed by state legislators, not directly by voters. Thanks in-part to increased tensions with France following the Jay Treaty, Thomas Jefferson won. He followed Washington’s lead and served for life, presiding over the Democratic-Republican dominance of the 1810s. HIs death in 1826 symbolized the passing of the Founding Fathers’ generation. With no clear successor, there was a brief period of chaos, ultimately ending in General Andrew Jackson’s ascension to the presidency.

What Did It Say About America?

That liberty had its limits. Voters, and Congress, couldn’t be trusted! America had a chance to form a totally new system of government, but it would ultimately fall back on monarchy.

Was It The Right Decision?

No! Washington’s decision to step down was not just important for the United States, but for the world. During the American Revolution, few people could even conceive of a government in which the head-of-state didn’t hold onto power for life. Today, in our timeline at least, it is expected that our leaders step down after a set term. That’s something we take for granted!

Images

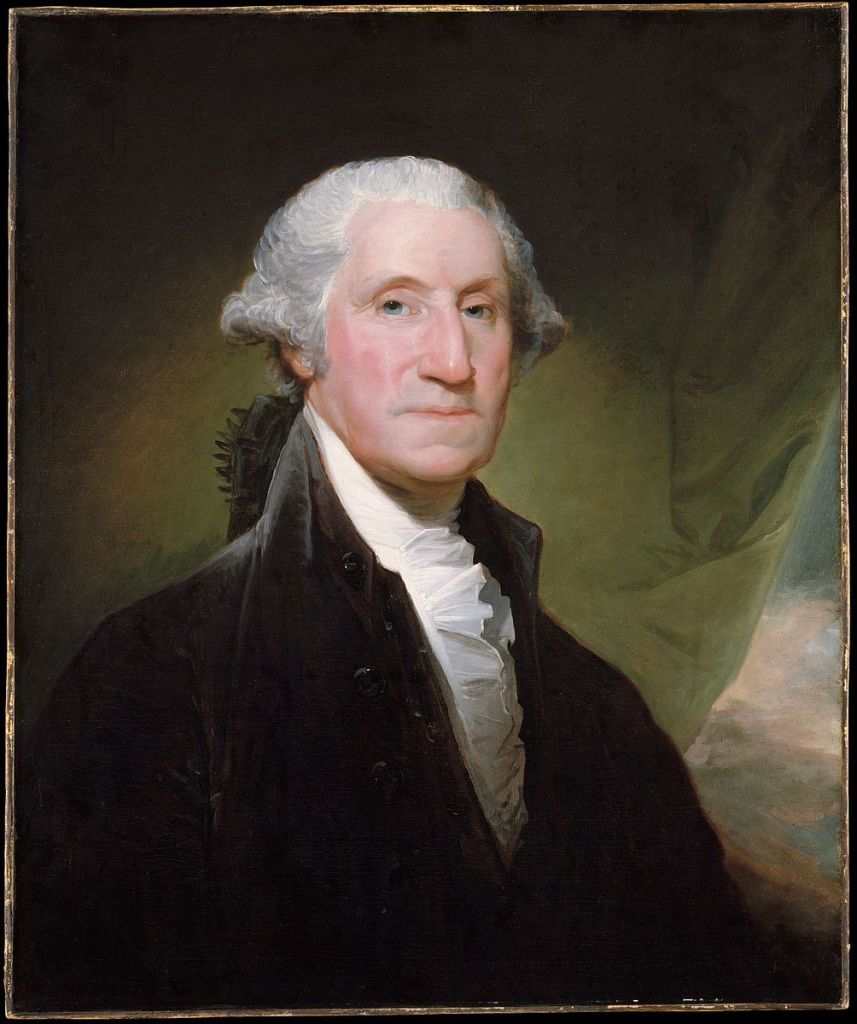

1. Portrait of George Washington, 1795 — Gilbert Stuart, Metropolitan Museum of Art / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

2. The Storming of the Bastille, 1789 — Jean-Pierre Houël, Bibliothèque nationale de France / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

3. Washington on his Deathbed, 1851 — Junius Brutus Stearns, Dayton Art Institute / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

4. The Apotheosis of Washington, 1865 — Constantino Brumidi / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Resources

Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. The Penguin Press, 2004.

One thought on “1796: George Washington vs. No One, III”

Comments are closed.