I’ve received the first transmission from the Elections-verse! We’re starting all the way back at the beginning! The first election in this alternate universe was… wait, this can’t be right. There was no election? Where’s George Washington? Oh my god… in this timeline the Constitution never existed!!

The Last Four Twelve Years

On July 4, 1776, America declared its independence from Great Britain. The Revolutionary War inspired a new nation! There was just one minor detail that the Continental Congress had overlooked — they technically had no formal authority over the colonies. The Founding Fathers needed to quickly establish a central government to handle the country’s affairs. A united American government had been proposed before, like Benjamin Franklin’s Albany Plan, but mostly as a compromise by loyalists to keep the colonies under the control of the Crown. Pennsylvania delegate John Dickinson had already been leading a committee to write the nation’s founding document — the Articles of Confederation. He argued against the war and instead hoped that the Articles would strengthen the colonies’ political position against Britain. When the Declaration of Independence was approved by the Continental Congress before the Articles, he chose to resign and join the militia. The Articles of Confederation were finally completed on November 15, 1777, although they were not ratified by every state for over three years.

Major Issues

Given that the Founding Fathers were fighting a war against tyrannical rulers and high taxes, it made sense that the Articles of Confederation created an intentionally weak federal government. It consisted of only one branch, Congress, whose main duties were to conduct foreign relations, declare war, and create treaties. There was one representative from each state. Bills required 9 of 13 representatives to pass (a supermajority), and amendments needed to be unanimous.

The most critical flaw in the Articles was that Congress did not have the power to collect taxes. They could only ask for money from the states, but they had no means of enforcement. Already burdened with war debt, the states were not eager to pay up. This had a large impact on the soldiers fighting in the Revolution. Washington struggled to supply his troops, forcing them to pillage the land of the farmers they were fighting for. The need for a stronger central government was evident to Washington, his officers (such as Alexander Hamilton), and a generation of young troops. After the war (yay, we won!), the situation only worsened. Veterans were unpaid and drowning in debt. The crisis culminated in Shay’s Rebellion, a months-long armed protest in western Massachusetts. By now, most Americans realized that a change was needed.

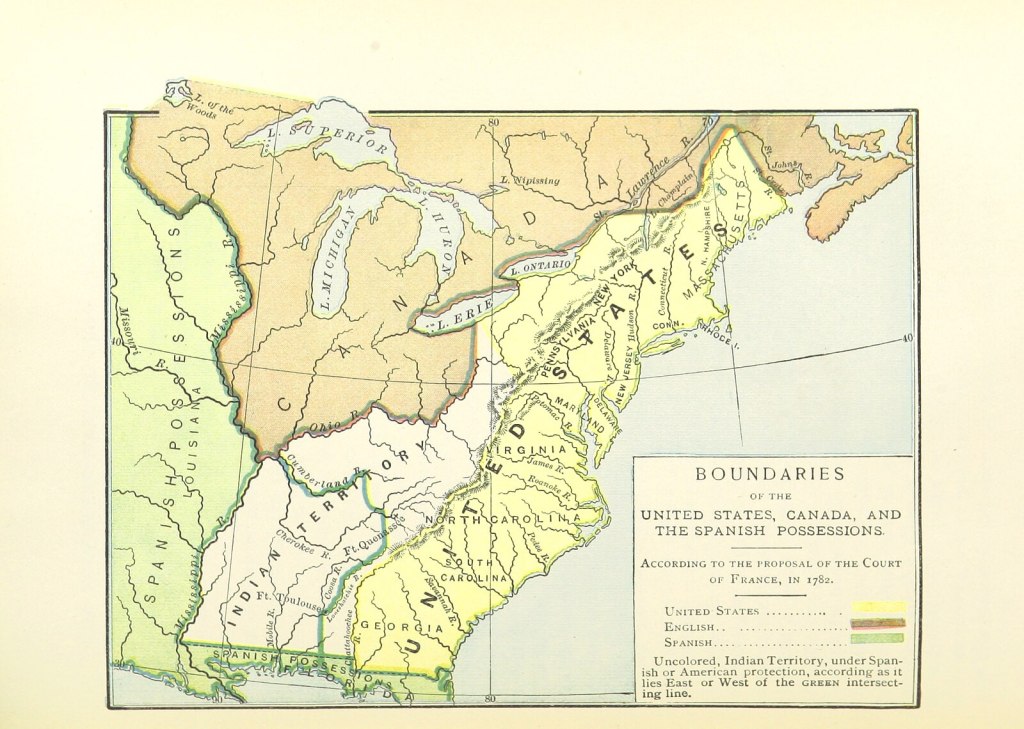

The US government under the Articles did have two major accomplishments, however — The Treaty of Paris (which ended the Revolutionary War on September 3, 1783) and the Northwest Ordinance. Along with a few preceding land bills, the Northwest Ordinance organized the northern lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. It outlined the path for new settlements to become territories, and eventually, states. Importantly, the original 13 states had to first relinquish their western land claims, which expanded far beyond their modern-day borders. This was a serious issue to smaller states, who had long been concerned about land-grabs from their larger neighbors (it’s why Maryland was last to ratify the Articles). The new states would be equal entities to the originals, not colonies.

A convention to amend the flaws of the Articles of Confederation began in May 1787. Soon, the delegates became convinced that an entirely new document, and a new form of government, was needed. George Washington was elected president of the Constitutional Convention. His leadership cemented his reputation as a nonpartisan moderator. The resulting Constitution was completed on September 17, 1787. It expanded the federal government into three equal branches: the Executive, the Legislative, and the Judicial. Because official political parties had not yet formed, the Framers were mostly concerned with creating a system of checks and balances between the branches. To satisfy both big states and small states, Congress was split into a bicameral legislature — two delegates per state in the Senate, and delegates proportional to their population in the House of Representatives. The Constitution needed to be ratified by at least 9 of 13 states to go into effect.

The Campaign

Supporters of the Constitution got to work promoting it in a series of essays known as the Federalist Papers. John Jay wrote 5, James Madison wrote 29, and Alexander Hamilton wrote the other 51! The authors outlined the details of the new document and why it was necessary. They argued that a strong central government would balance the competing interests of all of the nation’s factions, protecting them from the “tyranny of the majority.”

Those opposed to the new document were known as Anti-Federalists. They were concerned with abuses of federal authority and believed that most government powers should remain with the states. In some states, Anti-Federalists proposed a Bill of Rights to protect individual liberties against government overreach.

The Winner

The Constitution was quickly ratified by Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Georgia. The remaining states, however, demanded that the Bill of Rights be guaranteed to form a new government.

Unfortunately, in this alternate timeline, the two sides could not come to an agreement. In the outstanding state legislatures, the Federalists insisted that the Bill of Rights was not necessary. The Anti-Federalists were able to block ratification in just enough states to prevent the Constitution from taking effect. The Articles of Confederation remained remained America’s form of government.

The Future

The United States of America remained unstable. An angry, indebted population continued to spark violence across the country. The “tyranny of the majority” meant that the individual states could not compromise for the common good. The death knell for the Union came when the original 13 states, desperate for economic growth, resumed their western land claims. A complex web of alliances and enemies formed between them, often resulting in armed conflict. The federal government had no way to control the states’ actions. Eventually, the Continental Congress disbanded and the Articles of Confederation were voided.

As they pushed farther and farther beyond their original boundaries, the now-independent states also competed with European powers. Without the combined force of the United States in their way, Britain, France, and Spain had much greater influence on the Western Hemisphere. The French Revolution, and soon after, the Napoleonic Wars, only further complicated these foreign relationships. When northern states began fighting with British troops along the Canadian border and the Great Lakes, they were in a much weaker position to defend themselves. The War of 1812 re-established British dominance across the continent. While a weaker American government may seem like an advantage to Native American tribes, they instead had to contend with multiple nation-states, each believing it to be their “Manifest Destiny” to control the continent.

What Did It Say About America?

That it wasn’t meant to exist! The concerns of the individual states could not be reconciled with the need for a central government. The American continent was destined for a future of European-style territorial conflict.

Was It The Right Decision?

No! America has its flaws, but I quite enjoy living here! While the federal government hasn’t always made the best decisions, both in domestic and foreign policy, it’s clear to me that the continent would not have avoided the violence of westward expansion under the Articles of Confederation.

Images

1. George Washington, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing left, in silhouette, 1904 — Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

2. Articles of Confederation 13c, 1977 — U.S. Post Office; Smithsonian National Postal Museum / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

3. Alexander Hamilton making the first draft of the Constitution for the United States 1787, 1892 — Hamilton Buggy Company / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

4. The Old Northwest, with a view of the thirteen colonies as constituted by the Royal Charters, 1888 — Burke Aaron Hinsdale, The British Library / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain