Some Housekeeping

As you may have noticed, I was unfortunately unable to keep up with my plan to write a blog post every week imagining alternate outcomes to each presidential election. That was a big project that required a lot of research! Although I may not be able to commit to weekly posts, there is still a pretty big election coming up that has, unsurprisingly, made me want to talk about parallel moments in American history. I hope to one day return to the alternative histories idea, but in the meantime, I’m going to focus on a few topics I feel directly relate to our current, anxiety-inducing, situation.

In contemporary politics, it is usually considered a given that the incumbent president will seek a second term. But that wasn’t always the case! Of the thirteen presidents who held the office between 1841 and 1885, only Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant successfully sought and won second terms. Of course, some of those men didn’t get the chance, as their lives were cut short. Their replacements, often selected in order to appease extreme wings of their party, didn’t fare so well, either. They struggled to unite their constituents without a clear mandate. They never had a real chance at their party’s nomination for the next election. In this post, I’d like to explore the presidents who chose not to run again on their own accord. These men were popular enough to have been serious contenders for their party’s next nomination (though they may have faced primary challengers). For a variety of reasons — personal, political, and altruistic — they chose to give up power. But was it always the right decision?

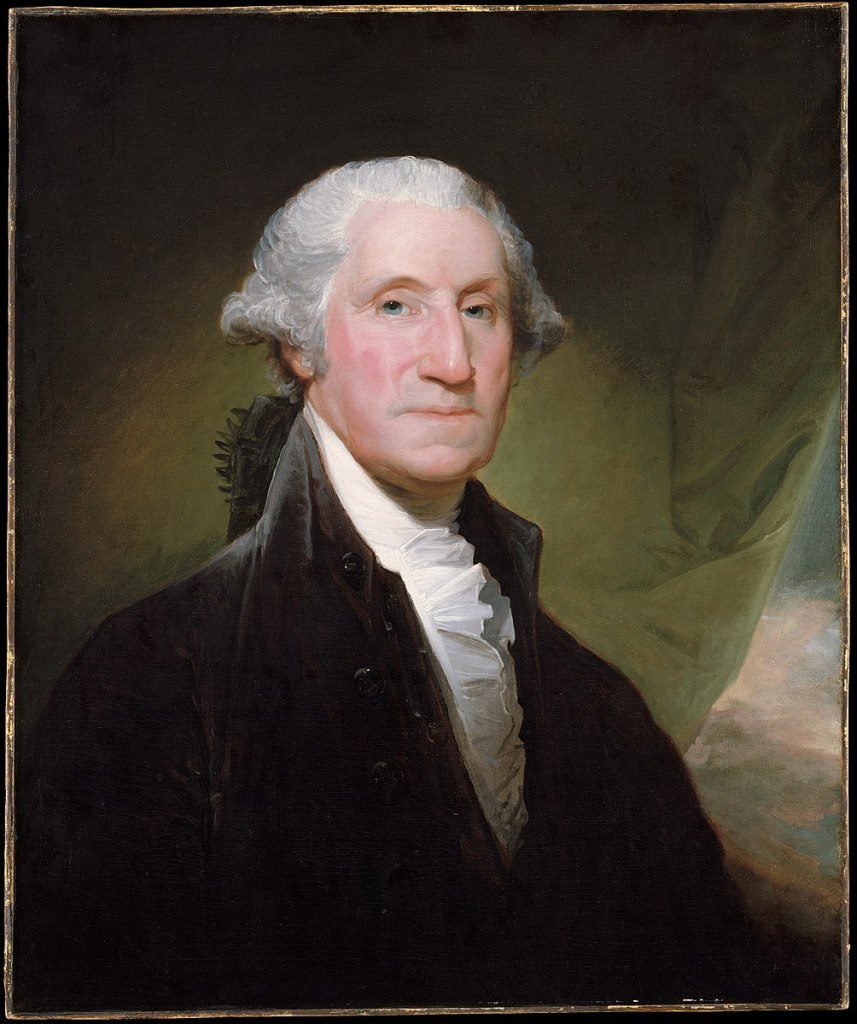

George Washington (1789-1797)

The man who started it all. Washington, famously, could have been America’s king. While it is difficult to imagine now, the idea that a country’s leader would voluntarily cede power basically was essentially unheard of in the Eighteenth Century. Many Founding Fathers, like Alexander Hamilton, once supported the idea of an American monarchy. Washington was unanimously elected by the electoral college in both 1788 and 1792. While his time in office wasn’t entirely smooth sailing, thanks to protests against taxes and growing tensions between Britain and France, Washington remained the most popular man in the country. He also maintained his independence as the rest of the Founding Fathers became sharply divided along ideological lines — laying the groundwork for political parties. Everything Washington did as president was being done for the first time, setting important precedents that shaped the role of the office. When Washington chose to step down after two terms, it signaled the democratic values of the new nation to the world.

How did it work out?

Good! America has, so far, avoided pure authoritarianism largely thanks to Washington. Other Founding Father presidents — Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe — followed Washington’s lead and each stepped down after two terms. It also worked out because Washington would have died during his third term in 1799, which would surely have set off a constitutional crisis that the country was likely unprepared for. The unofficial two-term limit remained the norm until Franklin D. Roosevelt’s four election victories during the Great Depression and World War II. In 1951, the rule was finally made law by the 22nd Amendment.

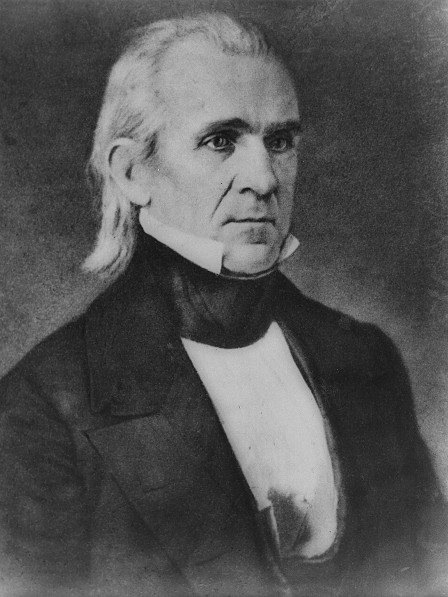

James K. Polk (1845-1849)

The first political party, as we know them today, was the Democratic Party, organized in support of President Andrew Jackson. After twelve years in power (two terms for Jackson, and one for his second-in-command, Martin Van Buren), Democrats left behind a nation in crisis. An economic depression in 1837 finally allowed the opposition party, the Whigs, to win the presidency. During the nominating convention in 1844, Democrats were still finding their identity without Jackson. They settled on the first dark-horse candidate, James K. Polk of Tennessee. Polk’s candidacy was centered on the annexation of Texas and the promotion of America’s Manifest Destiny to reach the Pacific Ocean. In the general election, he easily defeated Henry Clay, the Whig’s most prominent leader. Polk’s aggressive territorial expansion led to the Mexican-American War. Despite ongoing tension between the President and his generals, America won the war and acquired California and New Mexico Territories. Polk achieved everything he promised in one term and chose not to seek a second in 1848.

How did it work out?

As far as Polk was concerned, pretty good. Texas and the Pacific coast were part of America. Polk died shortly after leaving office due to contracting Cholera while on a tour of the South. Despite his success as president, the next Democratic nominee, Michigan Senator Lewis Cass, lost the 1848 election to war hero General Zachary Taylor. Both parties were becoming fractured by the question of slavery expansion in the new territories acquired by Polk. The country was on an inevitable path to civil war.

Rutherford B. Hayes (1877-1881)

Northern victory in the Civil War ushered in an era of Republican Party dominance at the federal level. After Lincoln, the party relied on General Ulysses S. Grant to finish the job of Reconstruction. Grant’s presidency had mixed results. While he held strong on the issue of civil rights for former slaves, his administration’s accomplishments were overshadowed by rampant corruption. Reform-resistant Stalwarts insisted that the Spoils System — the process by which party supporters were rewarded with patronage jobs in the government — was a necessary feature of party politics. Half-breeds, like 1876 Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes from Ohio, demanded change. Hayes won the general election against Democrat Samuel Tilden, but it came at a cost. In order to settle disputed election results in some states, Republicans agreed to end Reconstruction, allowing Democrats in Southern states to take back local power and impose Jim Crow laws. Hayes was indeed a reformer as president and set limits on patronage appointments. After one term, he was satisfied with his accomplishments and chose not to seek a second.

How did it work out?

The fight for party control continued. The 1880 Republican convention picked another dark-horse candidate from Ohio, Representative James Garfield. He won the presidency again for Republicans (their sixth in a row), but things looked bleak for reformers when Garfield was assassinated by a disgruntled office seeker just a few months into his term. Vice President Chester A. Arthur was one of the most corrupt politicians in the country. He previously served as Collector of the New York Custom House, the Stalwarts’ largest patronage machine. After taking office, however, Arthur had a sudden change of heart and enacted many of the civil service reforms that Half-breeds had been calling for. Republicans finally lost the presidency in 1884 to Democratic reformer Grover Cleveland of New York. He was the first Democrat to win a presidential election since the Civil War.

Teddy Roosevelt (1901-1909)

Born into a rich and well-known family in New York City, Teddy Roosevelt first rose to prominence as a reformer in the New York State Assembly. His national profile grew as he served as governor of New York and Assistant Secretary of the Navy — a position he resigned in order to lead the Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War. As a way to keep him under party control, he was selected as the running mate to fiscally conservative President William McKinley during his bid for a second term. The plan to contain Roosevelt backfired, however, when McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist less than a year after the election. As president, Roosevelt quickly became the face of the progressive movement. His uniquely personable and aggressive style of politics remade the image of the presidency. He won a presidential of his own in 1904, with the added promise that it would be his last term. Despite some reluctance, Roosevelt ultimately chose to keep that promise and handed the presidency off to his close friend and advisor, William H. Taft, in 1908.

How did it work out?

Teddy Roosevelt is unique on this list in that he very quickly regretted his decision to leave office. To be fair, he attempted to separate himself from domestic affairs by taking a prolonged tour of Africa and Europe. Soon, however, he began receiving letters from friends complaining that Taft had betrayed the progressive cause. Their accusations were largely exaggerated, but their impression on Roosevelt was dramatic. Upon returning to the US, Roosevelt threw his “hat in the ring” and declared his intention to seek the Republican nomination in 1912. Unfortunately for him, the party decided to remain loyal to their current leader, Taft. Never one to accept defeat, Roosevelt continued his campaign under his own Bull-Moose Party and adopted a radically more progressive platform than he had previously supported. His attacks on his former friend, Taft, were aggressive and often personal. Ultimately, they split the Republican vote, allowing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency. While Wilson also championed many progressive causes, his weakness on segregation allowed Jim Crow laws to fester and set the stage for a resurgence in KKK activity.

Calvin Coolidge (1923-1929)

The eight years of Woodrow Wilson’s presidency — which included a world war, an economic recession, a pandemic, and intense domestic unrest — left the country exhausted. The 1920 Republican ticket of Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding and Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge won the presidency by promising the country a “return to normalcy.” The economy slowly improved (though many felt that it was built on shaky ground), papering over several corruption scandals by Harding’s administration. When Harding died of a heart attack in 1923, Coolidge assumed the presidency and subsequently won an election of his own. “Silent Cal” had a more honest reputation than his predecessor. The economy continued booming and the Roaring ’20s were in full swing. Despite his success, Coolidge decided not to seek another term. He announced this at a press conference by handing out slips of paper reading, “I do not choose to run for president in 1928,” and left the room.

How did it work out?

It was probably for the best that Coolidge got out of there. The conservative economic policies of Harding and Coolidge contributed to the Great Depression. Coolidge’s successor, Republican President Herbert Hoover, was not equipped to properly address the crisis. The situation continued to deteriorate and Hoover lost his re-election bid to Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt. Like his cousin, Teddy, Franklin permanently remade the image of the presidency beyond conservatives’ worst fears. Under the New Deal, the power of the executive branch expanded greatly, and Democrats won five presidential elections in a row.

Harry S. Truman (1945-1953)

Another vice president that got an unexpected promotion. Truman was picked as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s final running mate in order to appease Southerners unhappy with the previous office-holder, progressive Henry Wallace. Truman wasn’t thrilled to accept the position, but he decided it was his patriotic duty to abide by the results of his party’s convention. Of course, shortly into Roosevelt’s fourth term, he passed away, leaving Truman to make the final decisions of World War II — including the decision to drop two nuclear bombs on Japan. America struggled in the immediate aftermath of the war. The economy was weak and tensions with the USSR were rapidly increasing. Most political observers believed Truman’s re-election loss to Republican Thomas Dewey in 1948 was inevitable. Instead, Truman pulled off one of the most surprising election upsets of all time by convincing voters that obstructive Republicans in Congress were the real problem. His second term had similarly mixed results, including a new war in Korea. Since the 22nd Amendment was established during his time in office, Truman was exempt. He strongly considered running for a third term, but after a disappointing start to the primaries, he chose to step aside.

How did it work out?

The 1952 Democratic nominee, Adlai Stevenson, was known for his wit, but it wasn’t enough to prevent his landslide defeat to General Dwight D. Eisenhower. In fact, he ran and lost again to Eisenhower four years later in 1956. Eisenhower was a moderate who oversaw a booming post-war economy. At the same time, The Cold War expanded, prompting Eisenhower’s use of covert military operations aboard, and the rise of anti-Communist radicals at home.

Lyndon B. Johnson (1963-1969)

Last but not least, Lyndon B. Johnson. Like Truman, he was selected as vice president in order to appease Southern voters. President John F. Kennedy had a bold vision for the country, but often fell short of enacting meaningful change. After his assassination, newly anointed President Johnson deftly used his predecessor’s legacy to fulfill his agenda — specifically, by passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Johnson easily defeated far-right Republican Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election and continued to pass progressive legislation like Medicare and Medicaid and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Unfortunately, these accomplishments were overshadowed by the Vietnam War. Tensions began under Kennedy, but it was Johnson who sent US troops. After years of fighting, American support for the war, and President Johnson, plummeted. Since he served less that half of JFK’s term, Johnson was eligible to run for re-election in 1968, but he faced tough primary challenges from JFK’s brother, Robert Kennedy, as well as anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy. The President shocked the nation by withdrawing from the race in a televised speech on March 31st.

How did it work out?

1968 was a tumultuous year. In June, Robert Kennedy was assassinated by Palestinian nationalist Sirhan Sirhan, leaving the race wide open. During the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, violence broke out between protestors and police. Despite the divisive backdrop, Vice President Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota won the party’s nomination on the first ballot. He faced Republican Richard Nixon and segregationist George Wallace in the general election. Humphrey struggled to separate himself from Johnson’s unpopular war strategy, allowing Nixon to prevail on a campaign of “law and order.” Although Nixon was relatively popular as president, he ultimately resigned in disgrace in the aftermath of the Watergate Scandal.

Concluding Thoughts

So, by my criteria, seven presidents had a real chance at serving another term but chose not to. They had mixed results. Washington set one of the most important precedents in US history. Polk and Hayes achieved everything they wanted to do, but left their parties fractured. Roosevelt regretted his decision and later split the Republican vote. Coolidge and Truman were satisfied and got out before things turned sour. And Johnson faced a tough primary in the most chaotic year in modern American history. For the most part, their decisions were signs of greater coalitional divides that were larger than the individuals in question. There’s no hard and fast rule as to whether a president should step aside or seek another term. That is, for better or worse, up to the candidate and those around them to decide. My best advice, if any of those people happen to read this blog, is to consider the mandate granted to them by voters at the start of their term, and whether that translates into another victory. Some presidents represent very specific goals to voters (annex Texas, enact civil service reforms, get us through a pandemic). Others have broader objectives (usher in a new progressive era, create a social safety net during an economic depression, protect democracy). The spirit of Washington’s two-term precedent is not that eight years is the perfect number. Rather, in a healthy democracy, aging politicians are regularly rotated out in order to make room for the next generation of leaders. We are not a monarchy, and no one has an inherent right to be president.

Images

I. Lyndon Johnson Addressing the Nation March 31, 1968 — Yoichi Okamoto, LBJ Museum and Library / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

II. George Washington, 1795 — Metropolitan Museum of Art / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

III. James Knox Polk, 1849 — Matthew Benjamin Brady / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

IV. President Rutherford Hayes, c. 1870-1880 — Matthew Benjamin Brady, Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

V. Theodore Roosevelt, 1915 — Pach Brothers, Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

VI. Calvin Coolidge, 1919 — Notman Studio, Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

VII. Harry S. Truman, c. 1947 — National Archives and Records Administration / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

VIII. Lyndon B. Johnson, photo portrait, leaning on chair, 1964 — Arnold Newman / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain