John Quincy Adams won the controversial election of 1824, and Andrew Jackson’s new Democratic Party immediately started campaigning for a rematch. Was there anything Adams could have done to stop them?

Background

The 1824 presidential election brought an end to the national unity of the Era of Good Feelings. Four major candidates competed to succeed President James Monroe: Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, Secretary of Treasury William H. Crawford, Speaker of the House Henry Clay, and Tennessee Senator (and war hero) Andrew Jackson. Since none of the nominees won a majority of the electoral college, the election was decided by the House of Representatives. Although Jackson had won the popular vote, Clay used his influence over Congress to ensure victory for Adams. Clay was soon promoted to Secretary of State, in a presumed deal that Jackson supporters labelled the “Corrupt Bargain.” They quickly began organizing for Jackson’s next presidential campaign,1 forming the basis of the new “Democratic Party.”

For better or worse, President Adams represented the old political establishment started by the Founding Fathers. Of course, his father had been president, too, and he had a long resume as a diplomat. As President Monroe’s Secretary of State, he was an obvious successor. Sure, he had not won the majority of votes on Election Day, but if Jackson didn’t have support from Congress, well that was simply a consequence of his outsider status. In fact, the Constitution was specifically written to prevent mob rule by temperamental voters. Adams represented unity and stability. As both Adams’ and Jackson’s factions had roots in the Democratic-Republican Party, the former transitioned to the label, the “National Republicans.”

The cornerstone of Adams’ policy agenda was the “American System,” first proposed by Henry Clay. It consisted of three parts: 1) Increased federal spending on infrastructure projects, 2) A strong National Bank to set monetary policy, and 3) High tariffs on foreign goods to protect American manufacturers. The plan was most popular in the industrial North and in areas of the West hoping for money to expand their economies. In the South, however, it was viewed as an extreme expansion of government power. Even some National Republicans felt that Adams was pushing the limits of his tenuous electoral mandate. Although a few infrastructure projects were funded (mostly canals), many of Adams’ plans were blocked when Democrats took control of Congress in 1826.

Major Issues

In many ways, the Democrats were the first modern political party. Importantly, New York Senator Martin Van Buren, previously a William H. Crawford supporter, flipped to lead Jackson’s re-election campaign. As more and more states chose presidential electors by popular vote (of white men), rather than by state legislatures,2 Van Buren knew that an appeal to common voters could remake the American political landscape. He carefully constructed a new coalition of anti-establishment outsiders and small-government ideologues (specifically, states’ rights slaveowners in the South). These voters agreed with Jackson’s assessment of government corruption. To them, the General was a self-made man fighting against elites like Adams. Many were also motivated by the long-lasting economic recession that followed the Panic of 1819, and the perceived failure of the National Bank to mitigate the damage. They argued that the American System wasn’t really an investment in the national economy, but rather another opportunity for corrupt politicians to gain more money and power.

Van Buren’s strategy extended to Congress, as well. Adams’ plan to raise tariffs was divisive among National Republicans. Not all of his supporters lived in industrial cities, and those in rural areas faced the heaviest burden from increased costs to imported goods. Democrats introduced a bill to raise the tariff to extreme rates (38% for goods, 45% for raw materials) in order to intentionally split their opposition. They assumed the bill would fail. Instead, the “Tariff of Abominations” was passed by Congress and sent to President Adams’ desk.

~The Alternate Universe~

Sensing the precarious situation his party had been placed in, Adams chose to veto the tariff bill.3 He knew that maintaining support from rural areas was more important to his re-election chances than appealing to industrial cities, who were likely to vote for him anyways. The tariff was toxic, and Adams needed to moderate his positions in order to achieve party unity.4

The Candidates

President Adams ran for re-election along with his Vice President John C. Calhoun. As a native South Carolinian, Calhoun’s endorsement validated Adams’ moderation.5 Together with Clay’s support in the West, the National Republicans were able to remain competitive with Democrats. The opposition ticket was, of course, represented by Jackson and Van Buren.

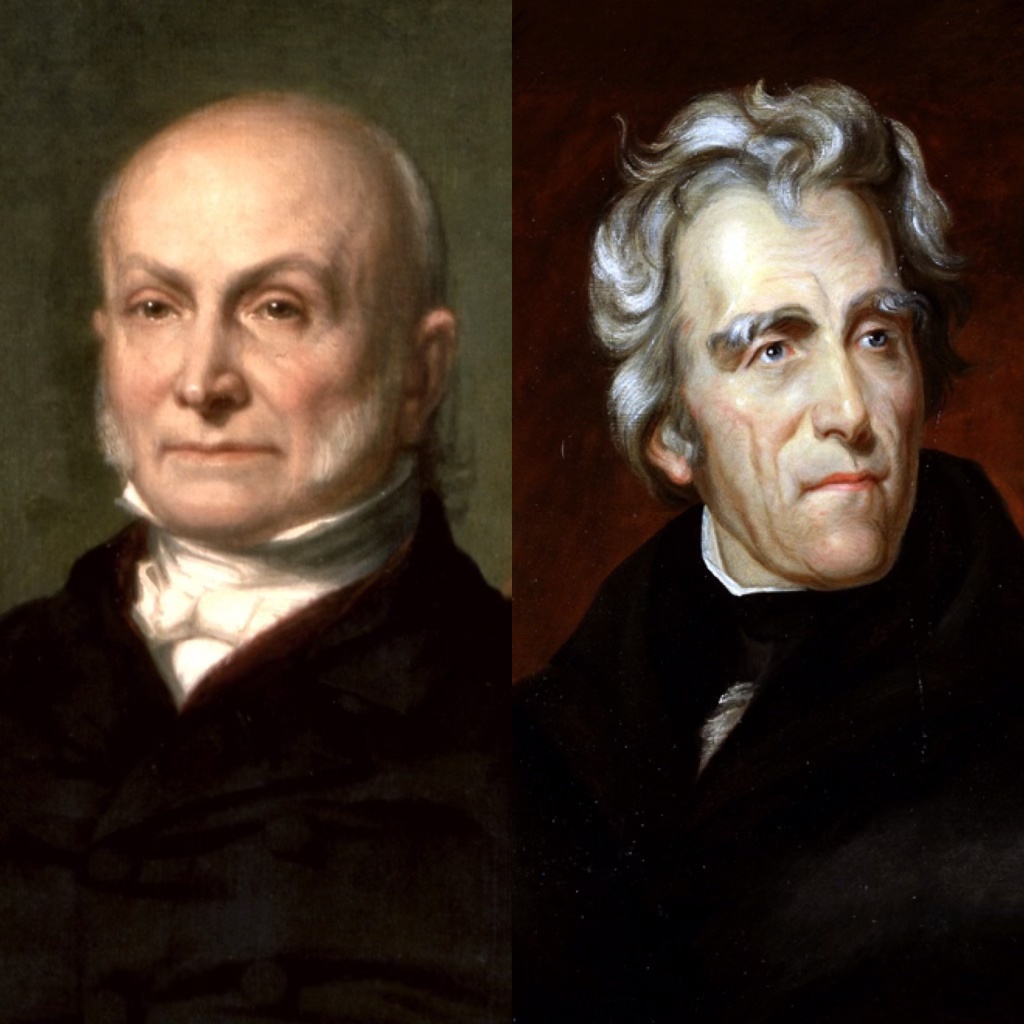

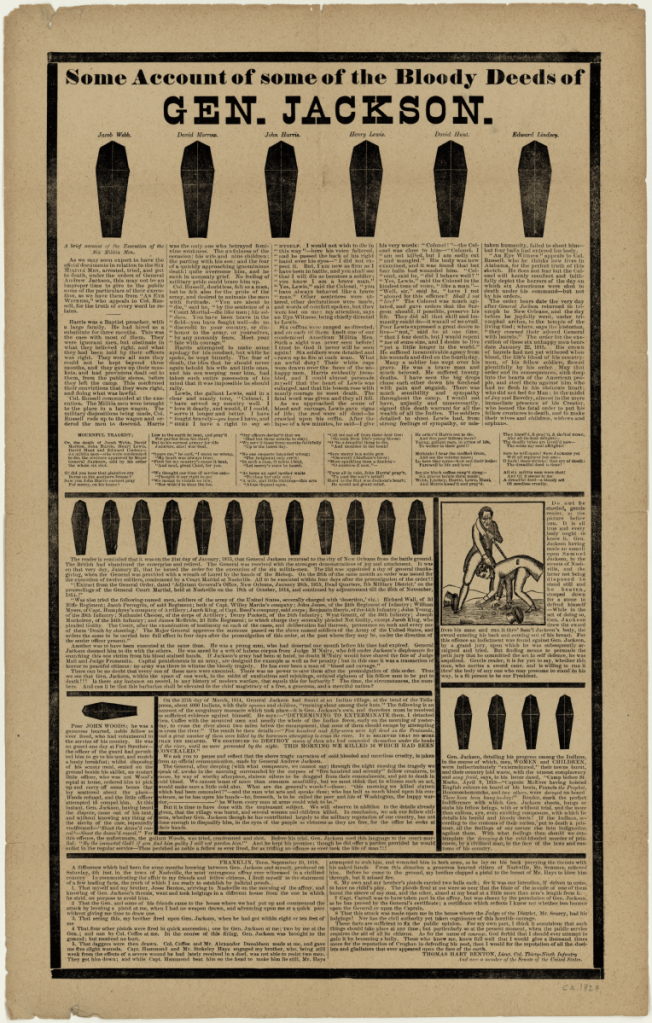

The 1828 campaign was a particularly nasty one. Democrats claimed that Adams, in his previous role as Minister to Russia, had procured women for the Czar. National Republicans got even more personal. In the “Coffin Handbills,” they questioned Jackson’s military record and violent reputation.6 The worst scandal, however, involved Jackson’s wife, Rachel. The couple had been unaware before their marriage that Rachel’s divorce from her first husband had not been finalized.7 Together, these controversies created an image of Jackson as crude and immoral.

The Winner

John Quincy Adams won! Although it was another close election, Adams’ partnership with Clay and Calhoun helped hold the National Republicans together. Their attacks on Jackson proved to just enough voters in swing states that the General could not be trusted with power. Unlike his father, Adams successfully served two terms as president.

The Future

Adams’ moderation came at a cost. The American System stalled. With domestic issues out of his control, Adams mirrored Monroe by focusing on foreign policy to cement his legacy. The alliance between Adams, Clay, and Calhoun formed a shaky coalition of anti-Jackson factions across the country, much like the Whigs of the 1830s-40s in our timeline. Also like the Whigs, it was unlikely to last, as western expansion forced debates over slavery that would split the country along regional lines. Ironically, without the Tariff of Abominations and the resulting Nullification Crisis (in which South Carolina argued for its right to invalidate federal laws), an important early debate over states’ rights went untested. In real life, President Jackson’s insistence that South Carolina had to comply was an important precedent cited by Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War.

What Did It Say About America?

The American political landscape was in a nebulous state. In our reality, Adams was too entrenched in the old ways of politicking. He never seriously attempted to unite his party. Jackson, and more so Van Buren, were ahead of their time. The popular vote was here to stay (and eventually expand!). Politicians would forever need to appeal to voters and could no longer rely on the impulses of a small ruling class.

Was It The Right Decision?

It would have been great if Adams’s vision for America had come to pass, but it just wasn’t possible at this point in history. The American System pushed the boundaries of federal power. Even with another term, Adams would have been unlikely to gain cooperation from Congress. Jackson’s presidency was inevitable, but their legacies tell a different story. After serving as president, Adams was elected to the House of Representatives (the only president to do so after their term) and became a strong anti-slavery advocate. His policies were eventually adopted by the up-and-coming Republican Party.

- Tennessee nominated Jackson for the 1828 election just a few months after Adams’ inauguration. ↩︎

- Delaware and South Carolina were the only remaining holdouts in 1828. Delaware would do so by the next election, but South Carolina would not adopt the popular vote until they rejoined the Union after the Civil War. ↩︎

- In our reality, Adams signed the tariff, sparking outrage amongst rural voters who conveniently ignored the Democrats’ role in its creation. ↩︎

- Adams, unfortunately, did not think like this. He had outdated beliefs about the presidency, party politics, and the government’s relationship with voters. ↩︎

- The real Calhoun was radicalized by the Tariff of Abominations, going so far as to claim South Carolina had a right to unilaterally nullify federal laws. He flipped to become a Democrat, but the resulting constitutional crisis caused a break between him and Jackson. Calhoun’s fight for states’ rights later made him one of the loudest pro-slavery voices in Congress. ↩︎

- This one is fair. Jackson killed a lot of people. ↩︎

- Sadly, Rachel died of a heart attack shortly after the election. Jackson forever blamed his political opponents for the stressful state that led to her passing. ↩︎

Images

I. The Monkey System — Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

II. John Quincy Adams, 1858 — George Peter Alexander Healy, The White House Historical Association / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

III. Andrew Jackson, 1824 — Thomas Sully / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

IV. Martin Van Buren, c. 1830 — Francis Alexander / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

V. Some Account of the Bloody Deeds of General Andrew Jackson, c. 1828 — Darlington Digital Library, University of Pittsburgh / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Resources

Hogan, Margaret A. John Quincy Adams. University of Virginia Miller Center, 2023, https://millercenter.org/president/jqadams. Accessed 26 November 2023.

Meacham, Jon. American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. Random House, 2008.