President James Monroe proudly presided over the end of the two-party system. But it wouldn’t last. To supporters of Andrew Jackson, the election of 1824 represented everything that was wrong with the corrupt federal government. Could there have been another outcome?

Background

Monroe’s re-election victory placed him in the exclusive club of presidents who ran uncontested campaigns (the only other member being George Washington).1 But the Era of Good Feelings papered over deep divisions that were forming in American politics. In 1820, Congress narrowly avoided civil war with the Missouri Compromise, though most observers understood that they had simply delayed the inevitable. Monroe hoped to tackle the ongoing economic recession with federal infrastructure projects, but faced heavy opposition from the Old Republicans in Congress, who disliked the President’s abandonment of their party’s small-government principles. This faction of “Radicals” believed a major transformation was needed to reset the status quo. They labeled Monroe’s supporters “Prodigals,” a derogatory reference to their willingness to spend government money.

Knowing that Congress was a lost cause, Monroe returned to his roots and focused on foreign policy. Along with Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, Monroe made important border treaties with America’s former rivals, Great Britain and Spain. With a little “help” from General Andrew Jackson (specifically, his not-so-constitutional capture of Pensacola), Monroe also successfully annexed Florida territory from Spain. With these treaties finalized, Monroe and Adams finally felt that the time was right to recognize the newly-independent countries of South America. Many Americans saw the revolutions in “New Spain” as spiritual successors to their own fight for independence, and hoped to benefit from new trade relationships. Some politicians also feared a European plot to stifle democratic movements around the world, following the end of the Napoleonic Wars.2 As a former diplomat, Monroe had watched his predecessors squander chances to improve America’s position on the world stage. After intense deliberation with his Cabinet, he issued what became known as the “Monroe Doctrine” to Congress in December 1823. In it, he declared an end to European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere, and announced that any attempt to re-establish control would be seen as an attack on the United States. This was a massive shift from George Washington’s insistency on American neutrality, which had become the status quo for decades.3

Major Issues

It was clear by early 1824 that Monroe had no obvious successor. While the opposing Federalists had been relegated to a regional party in New England, the many factions of the Democratic-Republican Party were each fighting for control ahead of Monroe’s departure. Monroe would be the last Founding Father to be president, and many candidates hoped to lead the next generation of American politics.

The Candidates

There were five major presidential candidates in the spring of 1824:

John Quincy Adams: Son of the former president and current Secretary of State. He had arguably more diplomatic experience than anyone of his generation. As a Massachusetts native, he was one of the only Northerners in the Monroe Administration.

William H. Crawford: Current Secretary of Treasury with close ties to Congress, having previously served as a senator from Georgia. He was the preference of the Old Republicans, especially in the South (including former presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison)4. Recent health issues caused many to doubt his ability to fill the role.

John C. Calhoun: Influential South Carolina politician who had impressed as Secretary of War (a job few wanted following the War of 1812). At the time, his views most closely matched Monroe’s.5

Henry Clay: Kentucky Representative and current Speaker of the House. He was one of the most skilled politicians of his era, and had played hardball with Monroe as retribution for not being selected for a Cabinet position. He campaigned on his proposed “American System” (strong national bank + infrastructure spending + protective tariffs) and his support was strongest in the West.

Andrew Jackson: Nationally celebrated hero of the War of 1812, currently serving as a senator from Tennessee. Most recently, he had invaded Spanish Florida, leading to its annexation by the US6. His outsider status and advocacy for small government earned him lots of support with voters — at a time when more and more states were selecting presidential electors based on popular vote.

Calhoun was the first to drop out. As a Southerner in the Monroe Administration, he alienated both the North and South. He instead ran for vice president, which he easily won.

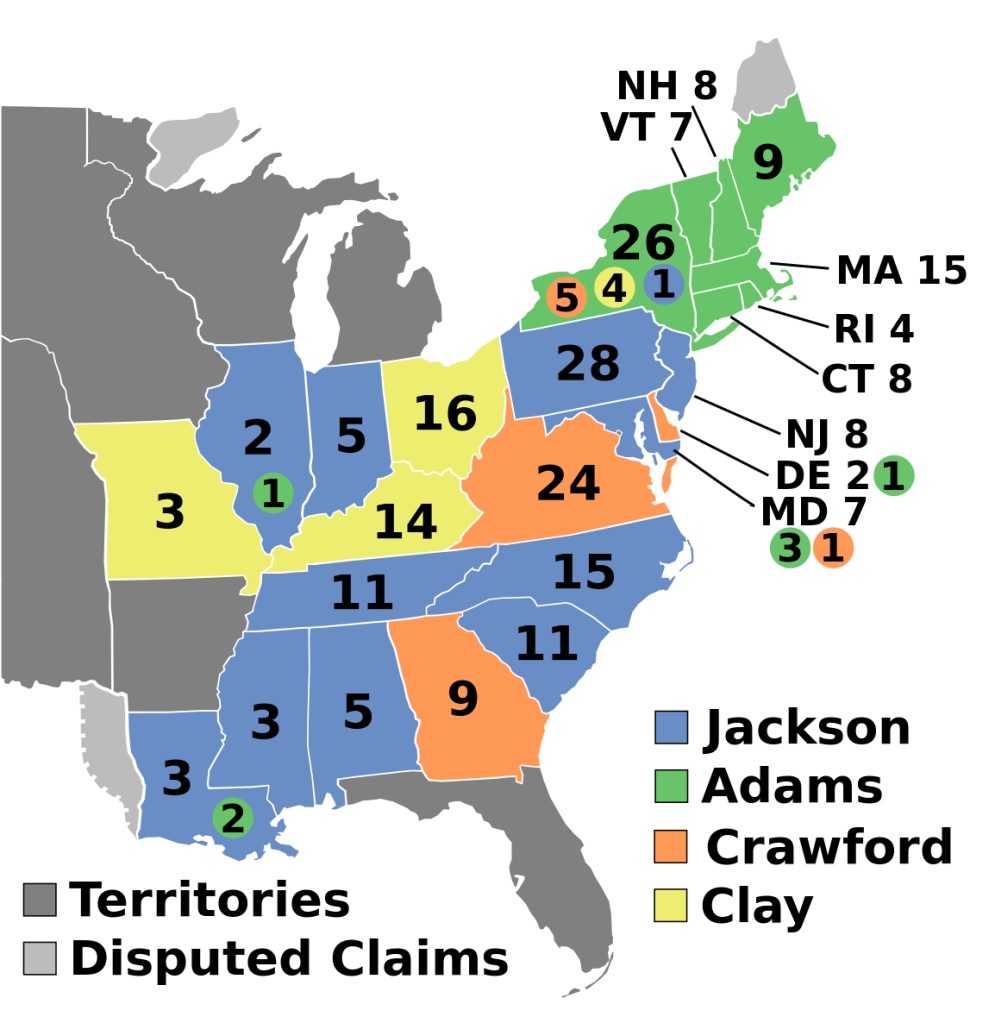

The presidential election results were split. Jackson won the popular vote, as well as the most electoral votes with 99. Adams’ 84 votes earned him second place, trailed by Crawford with 41, and Clay with 37. Because no candidate won a plurality of electoral votes, the election was to be decided by the House of Representatives — where Clay was conveniently in charge. Dealmaking consumed Washington until the vote in February.

~The Alternate Universe~

Although Clay and Adams had similar beliefs in the American System, the Speaker refused to grant his support to a political rival.7 The two had strong disagreements dating back to the War of 1812, as Clay had accused Adams of being too conciliatory towards the British. Always the cunning politician, Clay hoped that chaos between the North and South would give him a chance to become the palatable compromise candidate.8 Instead, it was the Jackson and Crawford factions that struck a deal.9

The Winner

After a few rounds of voting, Andrew Jackson won the House vote thanks to Crawford’s Southern supporters. Although no evidence of a deal was ever made public, Jackson appointed Crawford as his Secretary of State.

The Future

Jackson got everything he wanted as president — four years earlier than he did in our timeline. He built a coalition of small-government ideologues and rural anti-establishment voters. He blocked Clay’s attempts to institute the American System and dismantled the National Bank. Despite the economy’s sluggish recovery, Jackson won re-election against Henry Clay and a few other regional candidates in 1828. Importantly, in this universe, Jackson’s new Democratic Party did not start out as the opposition to President Adams. This meant that Jackson did not form as strong of a relationship with New York politician Martin Van Buren, the chief architect of the modern political party. Instead, Clay and the National Republicans (later renamed, the Whig Party) were able to remain competitive and defeated the Democrats in the 1832 presidential election. President William Henry Harrison ushered in a new era of increased government spending.

What Did It Say About America?

This ain’t your (Founding) Father’s party system. While people tend to underrate the intensity of the political divisions in early US history, this new generation would take partisanship to the extreme. In our timeline, Adams won the election with Clay’s help, but Jackson would enjoy the long-term victory. His Democrats would eventually dominate American politics for over a decade. If the Whigs had been forced to modernize four years earlier, they could have potentially built a stronger base and stuck around longer.

Was It The Right Decision?

No, but it was inevitable. Jackson’s loss in 1824 only proved to his supporters that the establishment was corrupt and evil. For better or worse, voters now had more power, and they saw Jackson as one of them. It would take a while for the new parties to solidify, but once they did, it would set the country on the path towards civil war.

- A common myth is that one elector (from New Hampshire) withheld his vote from Monroe to ensure that Washington remained the only president to win with a unanimous electoral vote. In reality, he simply disliked Monroe and his economic policies. ↩︎

- This included Russia, who wanted control of the Bering Strait, as well as the West Coast of America. ↩︎

- Monroe stopped short of forming official alliances with South America, as the monarchical plot never came to fruition. ↩︎

- Crawford was also the pick of the party’s caucus. He was disparagingly labeled “King Caucus” by opponents who felt the party’s influence was undemocratic. ↩︎

- Despite his moderate position within the party at this time, Calhoun would go on to become one of the most vocal pro-slavery politicians of his era, and a strong proponent of Southern secession. ↩︎

- Jackson was Monroe’s first pick to be Florida’s territorial governor, but the General got into a shouting match with the outgoing Spanish leadership (so intense that their interpreters couldn’t keep up) and resigned the position. In a letter to Monroe, he blamed his departure on bowel issues. ↩︎

- In our reality, Clay gave Adams his support and was rewarded with a new job as Secretary of State. Jackson and his supporters angrily labeled their deal the “Corrupt Bargain,” but it probably didn’t take much convincing for Clay to oppose Jackson. ↩︎

- This was actually a rumor about Calhoun, as some feared he had Aaron Burr-like presidential aspirations. ↩︎

- Monroe and Adams really were worried that Jackson and Crawford would work together. At this point, they considered both to be untrustworthy with power. ↩︎

Images

I. Caucus Curs in Full Yell, 1824 — James Akin, Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

II. Monroe Doctrine, 1896 — Victor Gillam, Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

III. Andrew Jackson, 1824 — Thomas Sully / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

IV. John Quincy Adams, 1818 — Gilbert Stuart, The White House Historical Association / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

V. William H. Crawford, c. 1810s — John Wesley Jarvis / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

VI. Henry Clay, 1818 — Matthew Harris Jouett, Transylvania University / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

VII. Electoral College 1824 — AndyHogan14 / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Resources

McGrath, Tim. James Monroe: A Life. Penguin Random House, 2020.

Meacham, Jon. American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. Random House, 2008.