Clinton and Crawford are back! In our reality, the Era of Good Feelings and Monroe’s uncontested re-election masked deep divisions across the nation. Could this have been the Union’s breaking point?

Background

The War of 1812 ended anticlimactically in 1815, with the US and Great Britain agreeing to return to the status quo. No major territory changed hands, but American patriotism was at an all-time high — thanks, in part, to General Andrew Jackson’s last-minute victory at the Battle of New Orleans.1 Many felt that the conflict represented a second war of independence. US victory (or, at least, a tie) reaffirmed its status on the world stage. Newly-elected President James Monroe took advantage of the Americans’ high spirits by embarking on the first-ever national presidential tour. In the summer of 1817, he traveled 3,000 miles over 110 days across the Northeast and Midwest.2 Officially, his goal was to assess America’s forts and defenses following the war, but at each stop, he was greeted with enormous excitement and fanfare. Many spectators realized that it was their last chance to see a Founding Father in-person.3 It was a rival Federalist newspaper that labeled Monroe’s time in office “The Era of Good Feelings.”

Not all of Monroe’s days were spent partying with townsfolk, however. With the Federalist Party effectively demolished at the national level (their anti-war stance had been the final nail in the coffin), it was internal divisions within the Democratic-Republican Party that drove Washington politics. Once the embodiment of small-government values, Monroe’s long tenure in the federal government had prompted him to adopt many of the Federalists’ best ideas — specifically, the National Bank, military investment, and infrastructure improvements. Although he was proud to have precipitated an unprecedented moment of national unity, he struggled to manage the many factions in Congress, some not so happy with his new ideological moderation. Speaker of the House Henry Clay of Kentucky was resentful that he had not been selected for Monroe’s Cabinet, and used his position to antagonize the President. Meanwhile, Monroe’s closest advisors — Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, Secretary of Treasury William H. Crawford, and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun — were all jockeying for position as his presidential successor. Monroe deeply valued their input, but each had their own ulterior motives.

From a policy perspective, Monroe’s first term saw mixed success. Unsurprisingly, given his past experience as a diplomat, Monroe placed great emphasis on foreign policy. With relations with Great Britain finally at-ease, America’s attention now turned to Spain. Many Democratic-Republicans believed that the US should recognize the ongoing independence movements in South America as spiritual successors to the American Revolution. Monroe felt that it was best to remain neutral, for the time-being. The more pressing issue was Spain’s lack of control in Florida, where Seminole tribes were crossing the border to attack Americans in Georgia. Monroe sent General Jackson to defend the border. Controversially, Jackson took an extreme interpretation of Monroe’s orders in order to attack and capture the city of Pensacola.4 Jackson acted irrationally, and likely unconstitutionally, putting the US at risk of war. It strengthened America’s negotiating position in the short term, but after some initial progress, Spanish approval of a border treaty stalled.

Monroe faced another major crisis at home. The Industrial Revolution had rapidly changed the global economy. At the time, Britain benefitted the most and quickly rebounded from the Napoleonic Wars. Mass-manufactured goods from Europe flooded American markets. Local businesses, and eventually banks, were devastated, leading to the Panic of 1819. That summer, Monroe took another national tour, this time in the South. The region had been hit hardest by the recession, as cotton prices plummeted. The President promised that the government was doing everything it could to help those affected, but given the limited powers of the federal government at the time, there was little he could do. In fact, many Americans blamed the National Bank for mishandling the economy. As another election year approached, Monroe worried that he had no accomplishments to run on.

Major Issues

The bill approving Missouri’s statehood was first presented to Congress in February 1819. It quickly drew controversy when New York Representative James Tallmadge introduced an amendment banning slavery in the new state. Missouri’s central location made it a uniquely contentious region. Nearby Indiana and Illinois had been admitted to the Union as free states, as slavery had been banned in their territories by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Of course, it was also close to the South, and any restrictions on slavery would greatly constrain the institution’s westward expansion. The issue was not resolved before the end of the legislative session, pushing the debate to 1820. Tallmadge did not win re-election and only served one term.

When Congress reconvened the following year, few expected Missouri to become a major issue, but it was soon the source of intense congressional gridlock. Southerners, led by Henry Clay, argued that no state should be admitted to the Union with restrictions that were not imposed on others. Missouri’s fate was tied to Maine, whose residents were looking to fulfill their long-held desire to separate from Massachusetts. Some Restrictionists in the North, such as New York Senator Rufus King, argued that the expansion of slavery was immoral.5 But many other Northerners simply feared growth of the South’s power over the federal government, and did not want to see the institution expand for political reasons. As the debate raged on, both sides believed secession was on the table.

After defending America from Great Britain and bridging the ideological gap between the parties, Monroe was now facing the greatest threat to the Union since its founding. Personally, he believed that Missouri should be admitted without restrictions on slavery (he was yet another Founding Father who denounced the practice morally, while still owning slaves himself), but he knew a compromise was the only path forward. He promoted a proposal to admit Missouri as a slave state, while banning the practice in the remaining territory above its southern border. He utilized aggressive tactics, like promises of patronage, to influence congressional leaders behind the scenes, hoping to reach a deal.

~The Time Warp~

The Missouri Compromise was not passed. Both Northerners and Southerners felt that ceding ground now would make them vulnerable in the future. Monroe had tried everything in his power, but his party’s fracturing was too much to overcome. Missouri’s statehood remained in limbo. Meanwhile, Maine’s chance at independence lapsed in March, forcing it to remain part of Massachusetts.6 Fierce debate continued throughout the year, while the presidential election loomed.

The Candidates

Despite his failure to maintain unity within his party and the nation, Monroe continued his re-election bid. He hoped that voters and electors would come to their senses and choose him as a way to reaffirm their belief in the Union. But many observers on both sides felt that the President symbolized the flaws in the Founding Fathers’ vision. Because they had not resolved the slavery issue earlier, it was now something that could end the Union entirely. It was time for a new generation to pick up the pieces.

Northerners coalesced around New York politician DeWitt Clinton. Although he had been unsuccessful in his 1812 split-ticket presidential campaign, Clinton still held a lot of power in his home state.7 He was known as a moderate (or, in a less flattering way, an opportunist), who could secure votes from both Federalist and Democratic-Republican Northerners. His candidacy confirmed many Southerners’ suspicions that the North wanted to block Missouri statehood, not because of their moral beliefs, but because they saw it as a way to reinvigorate the Federalist Party. They countered by nominating William H. Crawford. Crawford had long been seen as more ideologically-pure alternative to Monroe, and had close ties with Congress. As a Georgian, he could unite Southerners who were also tired of Virginia’s dominance of the executive branch. Finally, Henry Clay declared his candidacy in a long-shot attempt to improve his political standing. If the electoral results were split, he wanted to make sure his hat was in the ring. As Speaker of the House, he would be in a unique position to control the outcome.8

The Winner

DeWitt Clinton narrowly won an electoral majority. Votes split cleanly along geographic lines. Clinton’s strength was, of course, in the North, where the large electoral numbers of New York and Pennsylvania gave him a huge advantage. The South’s votes were split between the remaining candidates. Monroe became the first one-term president since John Adams, and the last Founding Father to be president.

The Future

As expected, the South was not happy with Clinton’s victory. Despite his promises of moderation, Southern states promptly seceded. Many Northerners were happy to see them go, but complications over federal property and control of the western territories prompted a civil war. DeWitt Clinton would face the greatest challenge of any president yet.

What Did It Say About America?

As noted throughout this post, the Era of Good Feelings wasn’t so good at all. Under Monroe, the ideological debates between Hamilton’s Federalists and Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans gave way to personal and geographic rivalries. Americans came out of the War of 1812 thinking they were stronger than ever, but the greatest crises lay ahead.

Was It The Right Decision?

No. Obviously, in an ideal world, the Missouri Compromise would not have been necessary. It saved the Union, but it was wrong. The problem was that DeWitt Clinton (or any of the other candidates) was not Abraham Lincoln. It’s difficult to imagine an acceptable ending to this story. In real life, of course, the Compromise did pass. Monroe viewed it as a political success and ignored the moral ramifications. In contrast, John Quincy Adams correctly concluded that they had only delayed the inevitable.

- The peace treaty had been signed weeks earlier, but Americans didn’t know it yet. ↩︎

- To honor the first president to visit their territory, Michigan renamed the settlement of Frenchtown to “Monroe.” ↩︎

- Monroe was known as “The Last Cocked Hat,” a reference to a Revolutionary-era hat style. ↩︎

- Jackson later argued that Monroe secretly told him to do it. ↩︎

- One of the last remaining Founding Fathers in government, King had also been a vocal opponent of the Three-Fifths Compromise in 1787. ↩︎

- It was Maine’s deadline for separation from Massachusetts that ultimately forced Congress to make a decision. ↩︎

- His candidacy was a real fear of Monroe’s. In actuality, he spent 1820 running for governor of New York against Vice President Daniel D. Tompkins. Clinton won and built the Erie Canal. ↩︎

- In fact, this is exactly what he did following the contentious 1824 election. Clay struck a deal with Adams (in the “Corrupt Bargain”), ensuring that the House would grant him the presidency, while he was appointed Secretary of State. ↩︎

Images

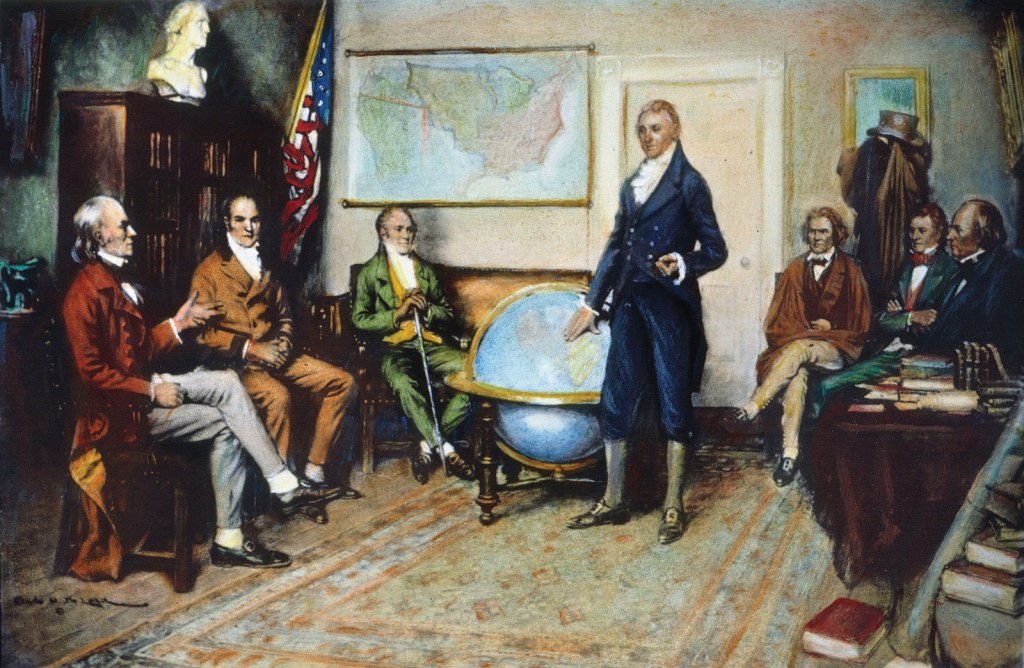

I. The Birth of the Monroe Doctrine, 1912 — Clyde O. DeLand, The Granger Collection / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

II. Independence Day Celebration in Centre Square, Philadelphia, 1819 — John Lewis Krimmel / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

III. Map of the Missouri Compromise, 1919 — McConnell Map Co. / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

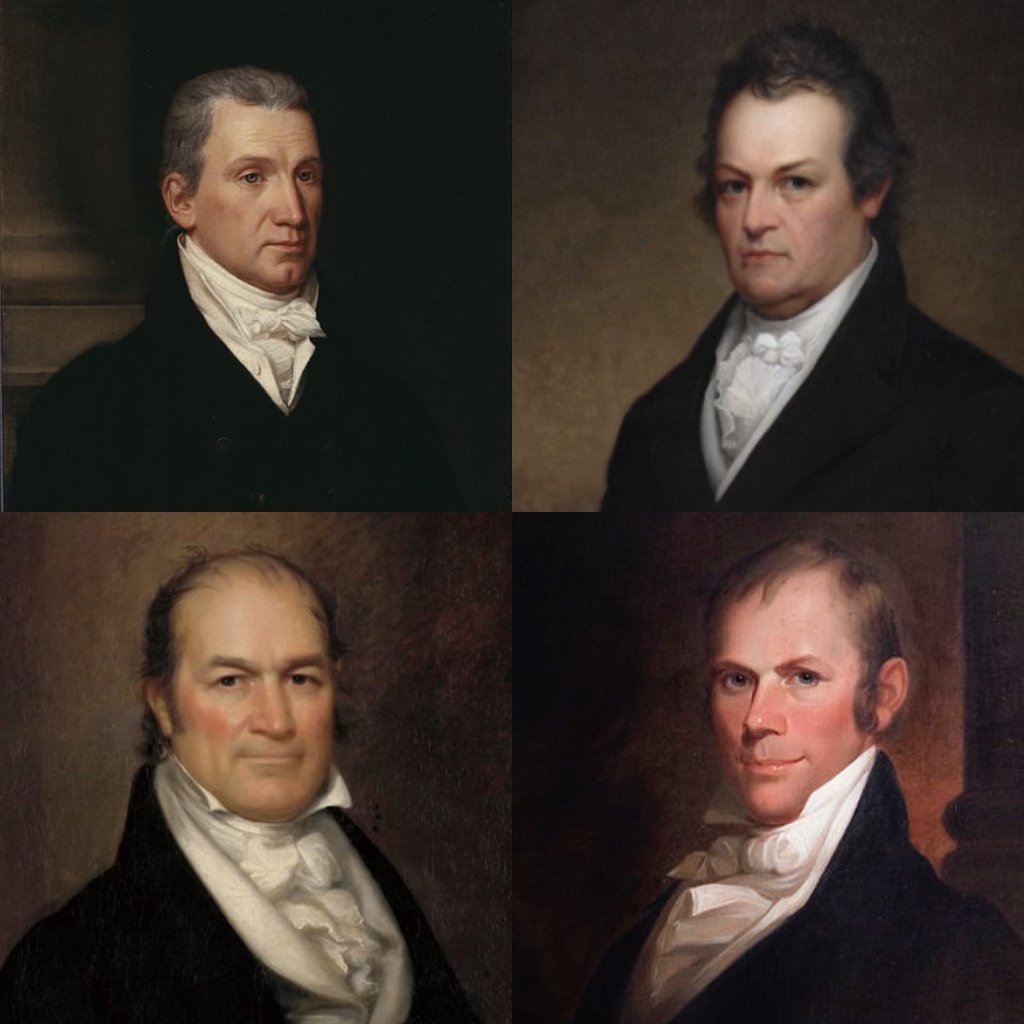

IV. James Monroe, 1816 — John Vanderlyn, National Portrait Gallery / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

V. Official Gubernatorial Portrait of DeWitt Clinton — Asa Twitchell / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

VI. William H. Crawford, c. 1810s — John Wesley Jarvis / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

VII. Henry Clay, 1818 — Matthew Harris Jouett, Transylvania University / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Resources

McGrath, Tim. James Monroe: A Life. Penguin Random House, 2020.