Despite earlier enthusiasm for armed conflict on both sides, the War of 1812 produced mixed results. The United States lacked troops, supplies, and money. If a few more things went the wrong way, it could threaten the stability of the Union…

For what really happened, remember to read my original post.

Background

President James Madison came into office in 1809 with the US and Great Britain already on the brink of war. British attacks on American merchant ships, as well as land disputes in virtually all directions, had empowered War Hawks in Congress to demand action. After some early fumbles, Madison made amends with former ally James Monroe and appointed him as Secretary of State. Together, they took an aggressive stance against Britain. The US declared war in the summer of 1812. Despite the loss of Fort Detroit, the USS Constitution‘s surprising victory in the North Atlantic helped keep Madison in office over split-ticket candidate DeWitt Clinton in the subsequent presidential election.

The war dragged on through the next two years. The US won major victories at the Battles of Lake Erie and the Thames (where General William Henry Harrison defeated Tecumseh), but advances into Canadian territory had failed. Meanwhile, the federal government was running out of money, thanks in part to the dissolution of the National Bank during Madison’s first term. With Napoleon’s defeat in Europe in early 1814, Britain was able to focus all their efforts on the American continent.

Madison continued to be plagued by controversy within his Cabinet. This time, it was Secretary of War John Armstrong who was hindering the war effort. Originally from Pennsylvania1, Armstrong served as a Senator for New York and Minister to France before joining Madison’s Cabinet. Importantly, he was the only northerner in the President’s inner circle. Armstrong had a reputation for being disagreeable and power hungry. He often feuded with the rest of Madison’s Administration, particularly Monroe, who shared in his presidential ambitious. When reports warned of a British attack on Washington, DC, Armstrong laughed it off, insisting that they would never invade the capital. Even as enemy ships entered nearby Chesapeake Bay, Armstrong argued that they were instead headed for Baltimore. He left the city totally defenseless. Monroe personally led a scouting party to investigate British movements, confirming that troops were already advancing on the city. After a short battle in Bladensburg, Maryland,2 American troops fled, leaving the capital in British hands. Although most citizens had already escaped3, British troops ransacked and burned government buildings, including the Capitol and Executive Mansion.

Armstrong, of course, took most of the blame. Militiamen taunted him and refused to shake his hand. Madison berated him, but stopped short of firing him, so as not to upset the North during a time of crisis. Instead, Armstrong agreed to take a leave of absence, leaving Monroe as interim Secretary of War. On his way out of town, he issued his resignation via the Baltimore Patriot, blaming the attack on Washington on the militia. Monroe’s new position was made permanent and he quickly made changes. Despite his longtime support of small-government republicanism, he embraced many ideas first proposed by Federalists in order to win the war.4 Specifically, he endorsed re-establishing the National Bank and forming a standing national army. Meanwhile, the American victory at Baltimore5 seemed to have turned the tide of the war. Diplomats in Europe hoped that a peace treaty could be reached soon. Madison proposed returning to the status quo.6

Major Issues

New Englanders had long been critical of Madison’s War. Reduced trade with Europe had been devastating to the local economy. They had little interest in fighting Canada, their northern neighbor, and had seen little success in nearby battlefields anyways. The presidency had long been dominated by Virginians like Madison, and by extension, the South. The North’s only representation in his Cabinet, Armstrong, had been replaced by Monroe, another Virginian, who was Madison’s heir apparent. Leading Federalist politicians called a meeting in Hartford, Connecticut, to discuss the crises facing the nation. Rumors quickly spread that the attendees of the Hartford Convention were plotting to secede from the Union. Madison sent investigators to New England and readied nearby militias in the event of an uprising.

~The Time Warp~

The rumors were true!7 The New England governors at Hartford agreed to leave the Union and join Canada. The war with Britain was now a civil war. While the British had previously been receptive to Madison’s peace talks, they were now incentivized to continue fighting. The conflict raged on.

The Candidates

Without New England, southern Democratic-Republicans had almost complete control of the federal government.8 The new political dividing line was support for the Madison Administration. Loyalists to Madison backed Monroe as their next presidential nominee, but his connection to the long and unending war was now a detriment to his political future. Furthermore, his embrace of Federalist policies like the National Bank and a standing army shattered his reputation as a true Jeffersonian.

The “Old Republicans,” still true to their small-government roots, opposed Monroe and instead backed William H. Crawford of Georgia. Like Monroe, Crawford had a long resume. He served as President Pro Tempore of the Senate before being selected as Minister to France during the war.9 By virtue of being in Europe for most of the conflict, Crawford had not been forced to take positions on issues like military funding and staffing. His former connections in Congress made him very popular in Washington, particularly with politicians from the South and West.10 Crawford was paired with New York Governor Daniel D. Tompkins11 as the vice presidential nominee. Tompkins was eager to end Virginia’s grip on the presidency, and was attractive to moderate northerners. Their ticket received an additional boost of support when John Armstrong wrote a pamphlet outlining Monroe’s personal and professional failures.12

The Winner

William H. Crawford won! The perceived failure of the war, in addition to his embrace of big-government policies, alienated Monroe from the Democratic-Republican base. Crawford’s support in the South and West boxed out Monroe from expanding his support. Virginia’s hold on the presidency finally ended, although the South still had all the power.

The Future

Brutal fighting continued between the US and the British-backed New England states.13 Soon after Crawford’s inauguration, a stalemate was reached. As both sides were drained by the economic hardship of the war, they reached a peace deal in summer 1817. While the US maintained control over disputed territory around Florida, the Mississippi River, and the Great Lakes, they allowed Canada to annex New England. Many southern politicians viewed the North’s secession as a long-term victory, as the slave states now had little opposition in the federal government.

What Did It Say About America?

The War of 1812, while not particularly famous in our present day, was an important test of national unity. The Federalists at the Hartford Convention didn’t really propose secession, but anti-government sentiment was very high in New England. The idea that the North had originally been more likely to leave the Union than the South is a surprising reality that contradicts our typical understanding of the time period. In real life, although no territory was won or lost in the War of 1812, the US ended on a high note with General Andrew Jackson’s victory at the Battle of New Orleans. Patriotism spiked and the anti-war Federalists suddenly looked like traitors. The party paid a steep price and effectively disbanded at the national level. It would be almost ten years before the Democratic-Republicans faced another opposition party.14

Was It The Right Decision?

No! Without a doubt, America would be worse off without the New England states — for economic and social reasons. Slavery would surely expand westward. Meanwhile, tensions would likely remain high between the US and Canada/Great Britain. In our reality, President Monroe settled additional border disputes with Britain (such as setting the rest of the northern border at the 49th parallel). It’s difficult to imagine that could have been accomplished if the War of 1812 ended on bad terms. Another armed conflict would not have been out of the question.

- During the Revolutionary War, Armstrong served in the Continental Congress. He would later be its last surviving member, and the only one to have been photographed. ↩︎

- Bladensburg was known for its lax policy on dueling, making it a hot-spot for politicians looking to settle disputes. ↩︎

- First Lady Dolley Madison, along with her servants and slaves, famously saved several historically significant objects at the Executive Mansion, including a portrait of George Washington. ↩︎

- Monroe even admitted to Jefferson that he had moved beyond partisanship and simply wanted to save the Union. ↩︎

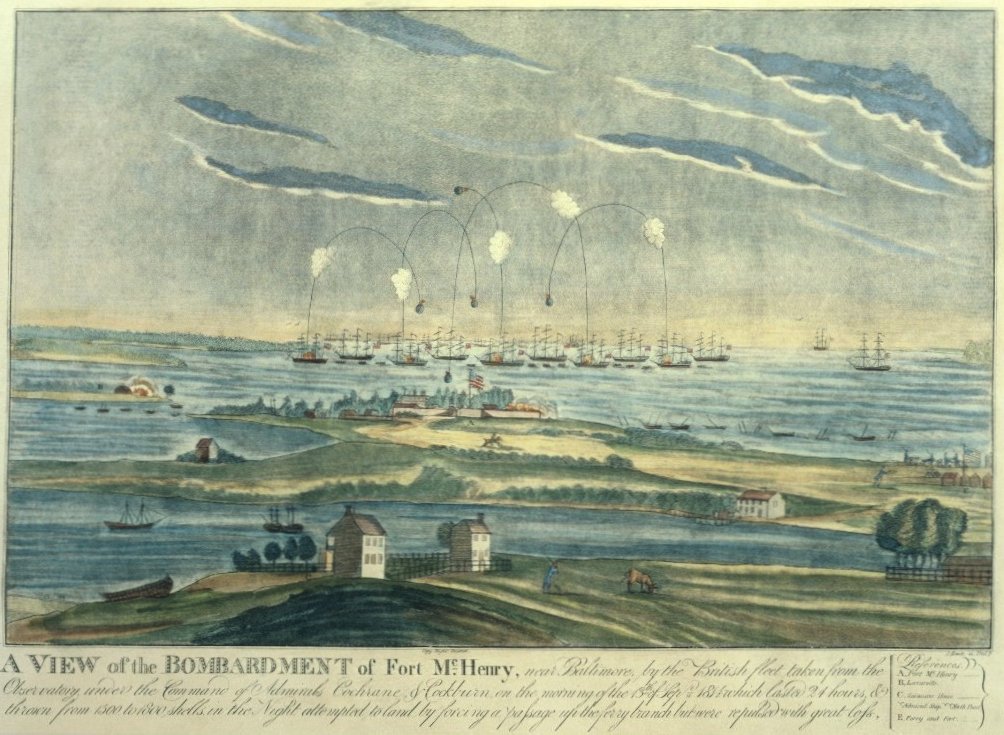

- Francis Scott Key was on a British ship arranging a prisoner exchange while this battle unfolded. At dawn, he was so relieved to see the American flag flying over nearby Fort McHenry that he wrote a song about it! ↩︎

- Ironically, this essentially was the same as accepting the terms of the failed Monroe-Pinkney Treaty of 1806 that had caused the rift between Madison and Monroe years earlier. ↩︎

- The rumors were not true. The Hartford Convention mainly spent their time reaffirming their policy beliefs and criticizing the South. ↩︎

- In our timeline, where New England remained part of the Union, the Federalists knew they had no chance of winning the presidency. They did not hold a nominating convention and backed New York Senator Rufus King by default. ↩︎

- When the War of 1812 ended in our universe, Crawford replaced Monroe as Secretary of War, as the latter was still also acting Secretary of State. ↩︎

- Crawford really was considered for president over Monroe by the Old Republicans. He was gaining momentum, but made the inadvisable decision to publicly decline his candidacy in order to stay on good terms with Monroe. Without the ability to openly campaign, his supporters struggled to expand his base. ↩︎

- In real life, Tompkins was picked to be Monroe’s VP. ↩︎

- Armstrong did this in real life, too. It was distributed amongst Federalist newspapers, but did not have a major effect on the election. ↩︎

- Even in our reality, General Andrew Jackson promised to personally hang any traitors in New England. ↩︎

- The Era of Good Feelings! ↩︎

Images

I. British Burning of Washington, 1816 — Paul M. Rapin de Thoyras, Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

II. A View of the Bombardment of Fort McHenry, 1814 — Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

III. The Hartford Convention or Leap No Leap, 1814 — Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

IV. William H. Crawford, c. 1810s — John Wesley Jarvis / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Resources

McGrath, Tim. James Monroe: A Life. Penguin Random House, 2020.