The turn of the century also symbolized a shift in political power. Democratic-Republicans labeled Thomas Jefferson’s presidential victory the “Revolution of 1800.” But Jefferson’s second term did not go as smoothly as his first, threatening the stability of his party. In our reality, this led to the War of 1812. Could things have gone differently?

Background

As president, Jefferson was not the small-government radical that many Federalists feared (and some Democratic-Republicans hoped). After spending years opposing Alexander Hamilton’s1 financial policies, Jefferson decided to keep the national bank in-place.2 Even more surprising, he greatly expanded the power of the executive branch with the Louisiana Purchase. Jefferson’s desire to gain more land for American farmers outweighed his concerns about government overreach. But one faction of the Democratic-Republicans felt betrayed. Known as the “Old Republicans,” they were frustrated that Jefferson was not living up to the ideals that formed the basis of their party.

Jefferson’s second term was clouded by rising tensions with Great Britain. Unsurprisingly, Britain was once again at war with France. Their conflict spilled over to the Western Hemisphere, as the British Navy began attacking American ships too. They were often looking for British deserters, but also forced many Americans into military service, a practice known as impressment. Americans were understandably angry. When similar issues arose under Washington’s administration, war was avoided thanks to the controversial Jay Treaty. Jefferson and his right-hand man, Secretary of State James Madison, knew they needed a skilled negotiator to deal with the British. They asked James Monroe, fresh off of arranging the Louisiana Purchase, to travel across the English Channel to begin peace talks.

Like Washington, Jefferson, and Madison, James Monroe was born in Virginia and owned a plantation with slaves.3 He served in the Continental Army during the Revolution, studied law, and became active in Virginia politics as an anti-Federalist.4 He previously served as Minister to France under Washington, before becoming governor of Virginia. While negotiating the Louisiana Purchase, Monroe had to carefully manage the interests of Jefferson and Madison, the French, and his fellow American diplomats. Although the deal was a success (doubling the size of the United States), questions remained regarding America’s claims to Spanish West Florida. Upon his arrival to Great Britain, Monroe was happy to find that the Whig-led government5 appeared to be sympathetic to America’s concerns.

Major Issues

Despite Monroe’s optimism, Jefferson and Madison never gave him their full support. To ensure the deal went their way, they sent William Pinkney6, a shrewd lawyer from Maryland, to assist. Their lack of trust strained their relationship with Monroe. Despite this tension, the two diplomats were able to create the aptly named Monroe-Pinkney Treaty. The treaty expanded upon the previous Jay Treaty and resolved a lot of major issues, such as ocean borders and trade disputes. Importantly, however, it did not include an explicit ban on impressment. As Monroe and Pinkney wrote to Jefferson and Madison, the treaty wasn’t perfect, but they felt that it was an important starting point. The British diplomats had separately promised that the practice would be ended, but Monroe and Pinkney failed to provide written proof in their letter. Jefferson and Madison didn’t buy it. Without the impressment ban, they refused to submit the treaty for congressional approval.

Monroe felt betrayed by his bosses. He worried that they had missed the small window in which a peace treaty was possible. Soon after, the American-friendly Whigs were replaced in Parliament by the conservative Tories. Peace talks were further derailed when the HMS Leopard attacked the USS Chesapeake right off the Virginia coast. Monroe attempted to continue negotiations, but was once again thwarted by Madison, who demanded a response from the British regarding the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair. Frustrated with Monroe’s lack of autonomy, the British threatened to send a diplomat to deal with Madison directly. For Monroe, this was the final straw. It seemed that too many parties preferred war to compromise. He resigned his post and returned to America.

Once home, Monroe received a warm welcome from Jefferson and Madison, but it was clear that he played no part in their future plans for the Administration or the Democratic-Republican Party. Jefferson had responded to the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair with the Embargo Act, banning all foreign trade for American merchants. He hoped to weaken the British economy and force them back to the negotiating table. Instead, he mostly hurt American businesses, particularly in New England, and tensions only increased. Opposition to Jefferson grew under the label of the Tertium Quids (Latin for “a third something”). Some Quids, like Virginia Representative John Randolph, expressed interest in supporting Monroe for president. They wanted to prevent Madison, seen as Jefferson’s heir apparent, from securing the Democratic-Republican nomination. Monroe replied that he would not campaign for the job, but he would accept it, if elected.

~The Time Warp~

The Quids were careful to subvert Madison’s political skills.7 They nominated Monroe alongside Vice President George Clinton8 of New York in order to box out their rival from both the North and South. Another major Monroe supporter, General Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, provided campaign support in the West.9 Jackson was bitter that Jefferson had not taken Spanish West Florida, land he believed it was his job to invade. The Quids strategy worked. By coordinating opposition to Jefferson across multiple regions, they were able to block Madison and secure the party nomination for Monroe.10

The Candidates

Monroe’s nomination split Federalists, who had been struggling outside of New England since Jefferson’s victory in 1800. Many moderates saw him as the best option for ending Jefferson’s influence on the presidency, and further fracturing the Democratic-Republicans. Others believed Monroe’s association with the ideologically extreme Old Republicans would reinvigorate the Federalist Party. They renominated their 1804 ticket of diplomat Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (one of the few Southern Federalists) and former New York Senator Rufus King.

The Winner

Monroe and Clinton won!11 Even with Democratic-Republicans in disarray, the Federalists were too weak to mount a serious competition for the presidency. Monroe’s election mirrored Madison’s in our own timeline. He captured nearly all electors outside of New England.

The Future

As president, Monroe quickly repealed the Embargo Act and resumed negotiations with Britain. His victory was proof that America was serious about maintaining peace. The Monroe-Pinkney Treaty was reintroduced and approved by the Senate. War was avoided! However, Monroe could not escape criticism. Federalists attacked him for being too weak in his negotiations with Europe. They had a burst of support and were once again able to run a competitive presidential campaign in 1812. Unlike our own reality, the Federalist Party was able to survive to the next generation of politicians. Newcomers like Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams ran as Federalists with a Tough on Europe campaign.12

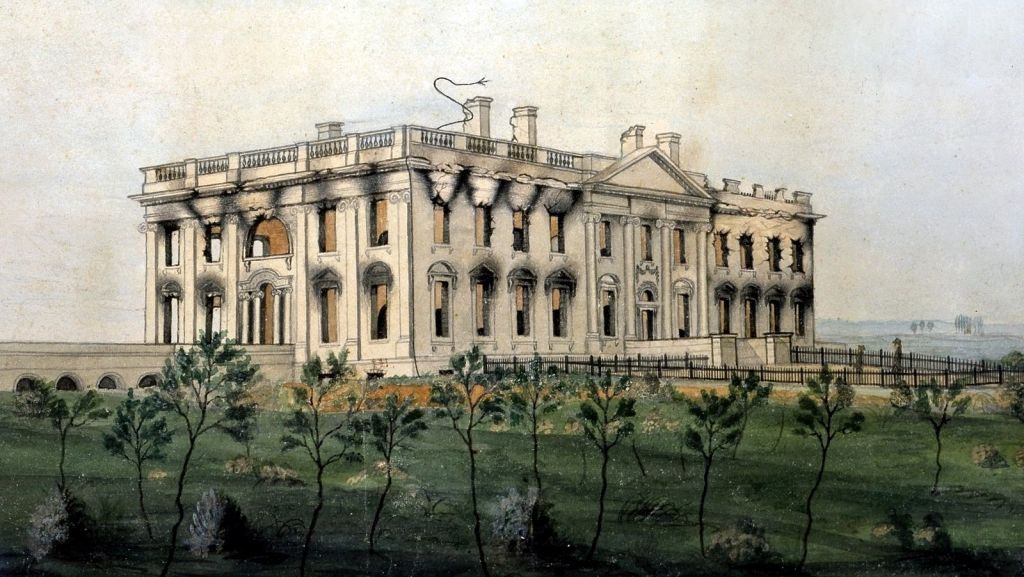

The War of 1812 never happened,13 but that meant a lot of patriotic symbolism disappeared with it. In fact, many Americans considered the war to represent a second war of independence, proving that America was here to stay. Without any major battles to win, a whole generation of generals (the celebrities of the 1800s) never gained national fame, including future presidents Andrew Jackson and William Henry Harrison. The Battle of Baltimore was never fought, meaning “The Star-Spangled Banner” was never written. But thankfully, Washington, DC, was never burned by British troops.

What Did It Say About America?

Jefferson’s Revolution of 1800 was real, but was limited to domestic policy. Federalists were right to criticize his blind hatred for the British. Monroe’s treaty could have prevented war, if Jefferson and Madison hadn’t micromanaged him. Fun alternate realities aside, by Election Day 1808, it was probably too late to prevent armed conflict.

Was It The Right Decision?

Mixed. Avoiding war is good! But Monroe in 1808 represented something very different from what he represented when he actually won in 1816. After the war, Monroe and the Democratic-Republicans moderated, absorbed parts of the Federalists, and ushered in the Era of Good Feelings.

- Hamilton dominated the first five posts in this series, but he met his untimely end following a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804. The Federalist Party would never recover without his leadership. ↩︎

- As stated in my last post, Jefferson considered ending the national bank, but his Secretary of Treasury regrettably informed him that Hamilton’s financial system was, in fact, good. ↩︎

- In comparison to other Founding Fathers from the South, Monroe was heavily critical of slavery, often supporting gradual emancipation. Later in life, he joined the American Colonization Society, which promoted sending free African Americans to new colonies overseas. Monrovia, the capital of Liberia, is named after him. Of course, he still owned many slaves throughout his life, and he spent most of his time as Virginia’s governor stopping slave revolts. ↩︎

- He voted against ratifying the Constitution. ↩︎

- Not to be confused with the American Whig Party, active from the 1830-1850s. ↩︎

- He is of no relation to the Pinckneys of South Carolina, who will be mentioned in this post shortly, and were often Hamilton’s preferred presidential nominees. ↩︎

- Madison’s greatest strength was actually his wife, Dolley Madison, who was one of the most skilled socialites of the era. ↩︎

- Clinton had presidential aspirations of his own, but at 69 years old, he was considered too old to be president. ↩︎

- In reality, many of his Monroe converts reportedly reverted to Madison when the fearsome general left town. ↩︎

- In our world, Monroe did not want to openly betray Jefferson and “pull an Aaron Burr,” as the kids say. ↩︎

- In both our reality and this alternate one, George Clinton was one of two VPs to serve under two different presidents (the other being John C. Calhoun). ↩︎

- In the lead-up to the War of 1812, Clay first gained notoriety as a “War Hawk.” He would later found the Whig Party in opposition to Andrew Jackson. ↩︎

- As the real 1808 winner, President Madison picked Monroe as his Secretary of State, after the two mended their friendship. ↩︎

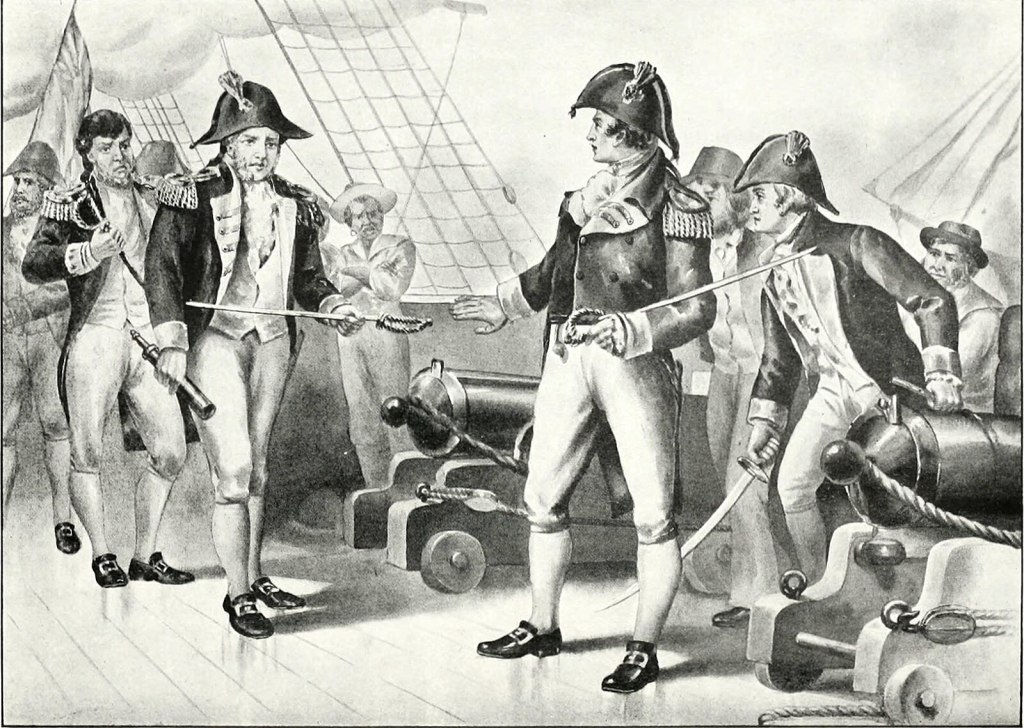

Images

I. James Monroe, 1816 — John Vanderlyn, National Portrait Gallery / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

II. Story of one hundred years : A comprehensive review of the political and military events, the social, intellectual and material progress, and the general state of mankind in all lands. Embodying detailed and accurate accounts of all things of importance and interest, from 1801 to 1900, inclusive, 1900 — Daniel B. Shepp, University of California Libraries / Wikimedia Commons

III. Ograbme, 1807 — Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

IV. The President’s House, c. 1814-1815 — George Munger, The White House Historical Association / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Resources

McGrath, Tim. James Monroe: A Life. Penguin Random House, 2020.